A Look Back at the Future

William Gibson on U2’s Vertigo Tour, 2005

May 2023

U2’s City of Blinding Lights

Pan across derelict concrete runway at dawn, somewhere in the American Southwest: Someone's unpacked the whole convoy of semis that haul the equipment for U2's Vertigo//2005 tour. Unpacked the lights and the behemoth speakers and the Wi-Fi cart for the backstage offices and spread it here, on the outskirts of some city from a '50s horror film where distance plays tricks on the eye. Every last piece of cargo has been set out, part of an angular, bilaterally symmetrical Rorschach blot - a hard-edged Mothra, inducing a faint deja vu.

The flat, interlocking plates of the stage are laid out like a game of solitaire.

Now the gear field stirs.

Scraping across oil-stained concrete, it bunches up anthropomorphically. Heaving up, Transformer-like, it comes alive, its shoulders the housings of giant speaker arrays, trailing epaulets of LED lighting.

Its eyes are clusters of surveillance cameras.

My wife and I stand in Seattle's KeyArena, noses level with the lower swoop of what U2 calls the Ellipse, the elevated stage loop the band traverses in performance. We're here because U2 is the early 21st century's biggest - and arguably most technologically innovative - touring group, the one that continues to define and redefine the spectacle that is arena rock.

For more than a decade, they've been driving both the technology and the form of the megatour while providing huge audiences with a powerful yet intricately managed sense of intimacy. I've been able to follow this, up close and backstage, on four other tours, beginning with ZooTV in 1992. Now I'm back, drawn by accounts of a lighter, more limber show. The remarkable continuity of U2's management culture allows for a genuine evolution, and the band members insist on it, so the odds of seeing something new are high indeed.

U2 is starting the sound check now.

I was born without a team-sports gene, I think, as I watch a technician pass Edge a Stratocaster in some shade of lacquer last seen on a Buick in Havana. For this reason, arenas have remained culturally mysterious to me. I can't remember ever having entered one, except for a rock concert.

Architect Mark Fisher, who led the design of the ZooTV set, introduced me to the intricacies of how a rock concert, a node of mobile architecture, can inhabit a sports arena - much as a hermit crab inhabits a seashell, it seemed to me. I hadn't thought of the design of rock tour sets as architecture before, but the idea of big, ambitious nomadic design erecting itself nightly within big, ugly concrete sports temples excited me mightily.

"William Gibson is in the house," Bono observes through the Vertigo sound system. The ghostly red Scalectrix of the Ellipse whips past us. We wave to him.

The confetti cannon takes me by surprise as U2 opens the concert with "City of Blinding Lights": glitzy, glittering, emotive kitsch. This glorious falling cloud is designer radar chaff, die-cut metallic PVC film. I pick some up, feeling like a rube at Roswell. The red rectangle is textured, the golden disc smooth, mirrored. Someone's worked these reflective differences out to get just this effect under exactly these lights. More crucial, though, the Vegas confetti storm is a bridge, a liminal device for the audience; we're over that threshold now, into the show.

The confetti serves as an opening act for the 12,000 individual spheres of the LED backdrop: daisy-chained pixel units that have unreeled from above while the chaff storm distracted us. Hanging behind and to either side of the band, these seven curtains can be retracted and lowered as needed, throughout the performance. They have a soft, slightly slinky, nicely organic look as they descend, the individual strands suggesting the bioluminescence of deep-sea fish. Fully extended, though, they do a fine imitation of Shinjuku on speed, and the lighting design for "City of Blinding Lights" takes advantage of that. Combined with the concentric LED rings of the target-motif stage and the ovoid light swoopings of the Ellipse, the visual effect manages to be far more that the sum of its parts.

During "Sometimes You Can't Make It On Your Own," Bono helps a young boy up onto the Ellipse. Arm in arm, he sings to him, as the boy, perhaps 10, sings right along. Everything's held in brilliant balance for an instant - in a sphere of almost tangible emotion - powerfully facilitated by this massive construct of highly specialized equipment. This stage, in the evolved efficiency of its various media, constitutes a vast amplifier for emotion. Bono and the boy, visible simultaneously on the Ellipse and as surveillance-camera images on the screens overhead, are fed back into the emotion of the crowd, which in turn comes up on the screens, a potent loop.

Steve Matthews, the affable, unflappable director of Principal Management, has explained that our exit tonight from KeyArena and the US, will take the form of "a runner." All nonessential U2 personnel will start clearing the building as the band leaves the stage for the first encore call. This has, I learn, everything to do with taxes. Unless they're aloft by midnight, they'll enter, as the IRS would see it, a new tax day.

While the crowd cheers for the first encore, we head backstage and fall in with decamping staff. There's something giddy about this as we exit enormous open gates and climb a steep ramp to a waiting row of vans. We pull out past a small crowd hoping for a glimpse of the band.

At Boeing Field, we stop near the target-painted tail of the Vertigo tour jet and scramble up the boarding stairs to un-uniformed flight attendants proffering wine and cold prawns. The first-class curtain up ahead has been drawn, and when we start taxiing to takeoff, I can only assume that the band is on the plane, having boarded via another set of stairs.

When I eventually make my way forward to talk with Edge, I glance around to see where they've stashed Bono. Under a seat? No Bono. As it happens, the singer is at this point on his way to Bill Gates' house for a sleepover, though I won't know this until I read it in the morning papers.

In the cabin, Larry Mullen is treating his drummer's elbow with a splendid high tech-looking box that pumps ice water through a tube and into a Velcro-fastened cuff. "They say it's NASA technology," he tells me. I ask if it helps. He shrugs. "I have a lot of machines," he says.

Someone I met in a Dublin pub opined that if U2 hadn't become the biggest rock act in the world, Adam Clayton might have become a policeman, Larry Mullen would have been the bohemian sort Clayton was perpetually chasing around town, Edge would have become an AI researcher, and Bono - well, it was impossible to imagine what Bono would have done if he hadn't gotten the job of being Bono.

This comes back to me, seated opposite Edge on our way up to Vancouver, as we discuss the band's idea of a U2 tour as a sort of traveling curatorial operation. The show incorporates elements from various artists - Julian Opie's light sculpture Walking Figures on the LED curtains and video art by Run Wrake, for instance.

"It's a co-op," Edge says of how the pieces of art come to be assembled into a unified show. "It's finding like-minded people who have something to contribute. Ever since ZooTV, we've found people who've got stuff, and we go delving through their collection of images. But in the end, all of the imagery is there to underscore what the music is already saying. It's a way to shed light from another angle."

How do they determine, given their eclectic style of assemblage, what ultimately fits and what doesn't?

"The acid test for us is whether something survives being in the show." He smiles. "Things sort of fall by the wayside."

Someone brings him a beer. So the touring environment itself is the testing ground?

"Touring will always be a very important aspect of what we do. When we're in the studio, getting close to finishing a song, you inevitably start thinking about how it's going to be performed. A song you don't think you'd play live, that's not a good song."

The tour's resident physiotherapist comes to remove Larry's NASA-tech elbow chiller, the closest thing I get to a warning that we're about to touch down.

We taxi to that weird corner of the Vancouver airport where Gulfstreams dock and deplane. Deborah and I are dropped at our house at 1 in the morning, ears ringing, feeling like Kansas children swept up by a benevolent tornado of rock biz and technology.

And here I dream of Vertigo's vast node of gear hunching itself into an enormous Dali-esque figure. Not the good Dali of museums, but the really wonderfully bad Dali of wartime necktie designs.

Waking, the deja vu message finally rings the memory bell: the back cover of Pink Floyd's 1969 album, Ummagumma, the one with all the gear taken out of their little van and arranged in a neat, symmetrical tableau - guitars, effects pedals, amps, mike stands, coiled cords. Generations of rock nerds have nodded, mesmerized, over that image, entranced by its perfect, fetishistic template.

The next afternoon, I'm down at Vancouver's GM Place, U2's next stop, to watch the load-in, the closest thing I'll see to Ummagumma-ing.

U2 rehearsed here a month ago, when the NHL strike provided a space they could rent for an uninterrupted stretch. There's a chill in the vast hollow of the place, from the ice covered with black sheets of rigid foam. My Converse slips on the rusty, sweating curve of the steel lip that edges the ice, and I wonder if that thing has a name in hockey.

The first truck to arrive gets labeled wireless with a cardboard sign. Matthews explains that they can't really do anything until the various species of wirelessness go operative: walkie-talkies first, then Wi-Fi for the gypsy office caves in the far backstage.

I ask Rocko Reedy, the band's stage manager, how he keeps track of all this stuff. "Big boxes," he says, pointing to the trucks, "with smaller ones inside, and smaller ones inside those." He shrugs.

"It's sort of like the military," offers one of the black-clad local crew, watching three of his fellows delicately manhandle a very large, wheeled box, "except there's less room to screw up."

As the riggers get to work, ropes drop from somewhere up in the girders.

I ask Jake Berry, the tour's production manager and the capo of all this, how he knows how to fit the Vertigo set into a given arena, since each venue has a different size and shape.

"I factor it in my head," he answers. "Bart Durbin, my head rigger, and Chuck Melton, one of the two riggers I have out here, have probably been here three or five or six times already. So somebody will go in and say, 'It's 120 feet to the low steel.' So once you know that, you know, and you've got 60-foot chains, so you know you've got to get 60 feet of steel. Then you work out how long the bridal legs are going to be." He looks at me, a man utterly at home with the crucial minutiae of a demanding trade, and for an instant I can almost imagine that he thinks I know what bridal legs are.

"In the end," he kindly simplifies for me, "It's really just experience."

Berry's experience began in 1975 with Yes, then six years touring AC/DC, on to the Rolling Stones, and now, all these miles and nights later, to U2 in GM Place. He reminds me of a character in one of those gritty spaceship films from the '80s: grizzled know-how and absolute authority in beat-up jeans and sneakers. He's the guy you hire if you need to be absolutely certain that your show will start on time.

"They're the start of your day," Berry says of the riggers, who I've seen, earlier, using lasers to sight the points of their rigging overhead. The builders of the pyramids would have loved those lasers. "If they're slow, your whole day's slow. If they're efficient, then your whole day's efficient. The first point of rigging goes up, and that determines where you are at 1 o'clock, and when you roll the stage, and when the band sound-checks." It all culminates that evening, in one more show.

Berry and his crew, I decide, are the real-life equivalent of my anthropomorphic dream giant: old-fashioned human intelligence and muscle, determined that the job will be done, and done right.

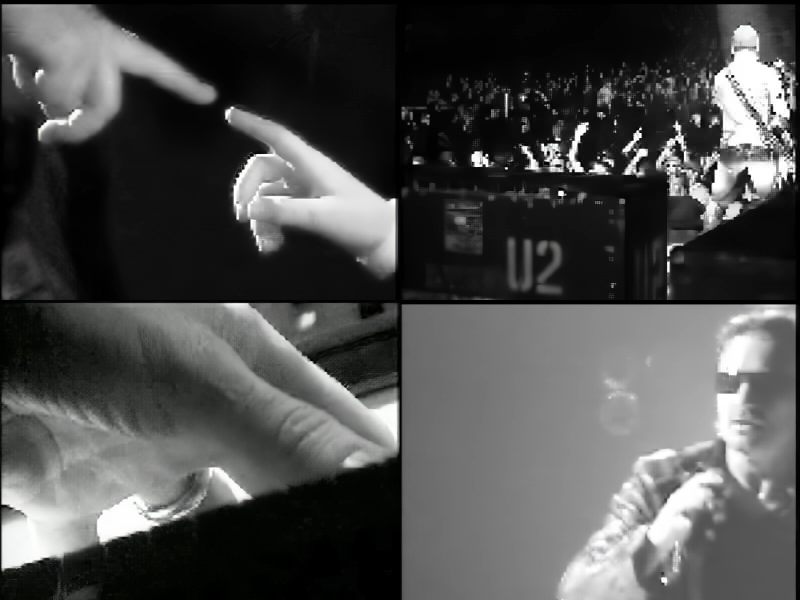

Willie Williams is this show's Man Behind the Curtain. Everyone tells me I have to see him, especially his collection of screengrabs from the remote-control surveillance cameras he's built into the Vertigo node to provide images for the giant scrim screens.

And truly, he doesn't disappoint. With sandy hair cut en brosse, the saturnine Williams combines a passionate delight in technology with an infectiously low tech joy. If his friend and sometime codesigner Mark Fisher is the least unhappy architect I've ever met, Williams is the least anxious big-ticket techno-designer. From Yorkshire by way of London punk, he met U2 in 1982, and the rest is entertainment history. His innovations have become industry standard. His cameras, he tells me, are capable of picking out eyelashes - in the dark.

"It's only about a week ago that I've started doing this," says Williams modestly as we watch a slide show of gorgeously lo-res surveillance stills on his PowerBook. "I'm trying not to be self-conscious about it. To begin with I was just playing, really. And they're quite difficult to control with a little PlayStation set, but that's all part of the joy of it. I'm trying not to overthink it." He had a PlayStation handset modified to allow him to control a number of small, infrared, black-and-white cameras, originally intending to use them to obtain covert imagery of the crowd, which he then mixes for display on the various screens above the stage. Mind you don't pick your nose at a U2 concert. Williams quickly discovered that his cameras offered him extraordinary views of the band in performance, and he's been happily collecting these at every show. "It's a great way of involving the audience. The physical nature of the set uses the fact that the audience wants to be part of the show."

Reminding him of his punk past, I ask where he sees this sort of technology going.

"What I'm enjoying," Williams tells me, "is that the technology is becoming affordable enough that younger bands are interested in doing something with it. At the end of the '90s, the live-music industry was dividing. There was the large-show, big-ticket nostalgia bands, the Eagles or whatever, but it wasn't anything to do with a rock show. That was where the production values were. The younger bands had no interest. Starting with Radiohead, though, I'm now seeing younger bands who are interested in the technology and where it can go. It's part of their language, really." He smiles. "When you've got cell phones that can make movies, it's suddenly not so gauche to put some energy into your visual presentation."

Williams leans back in his chair and grins. "We're thinking of webcasting concerts through U2.com, but part of the deal would be that subscribers could only watch us if we can watch them, through their home webcams, and then we'd all get to watch those images "

This time, I'm ready for the confetti cannon's glittery chaff storm ("airborne emotion," the Web site of a confetti-cannon manufacturer calls it). But my sense of the entire concert has been altered by watching how the Vertigo node travels and is assembled. Every last bit of the Ummagumma monster, I'm now aware, has had old-fashioned human energy applied to it, from Willie Williams and Mark Fisher dreaming of illuminated neural nets to Jake Berry and his laser-bearing riggers.

Following the final encore, Deborah and I make our way to the backstage caves. After a while, Edge comes in, looking remarkably unlike a guitarist who just played the concert he's just played, and takes a seat. Then Bono, who sounds quite raspy and has some postperformance energy to burn off.

Tonight's selection of an audience member for "Sometimes" hadn't gone quite as smoothly as it had in Seattle, and Bono recounts a few of his more dreadful experiences of this sort. "But the boy in Seattle," my wife reminds him, "he was perfect. He even knew the words."

An odd expression crosses Bono's face. "He was. Yes, he was. You know, I wrote 'Sometimes' for my father, and sang it at his funeral, and the boy, singing it to me it was as though I was my father " He falls silent for a moment, as if belatedly affected by the node's amplified emotion.

Willie Williams' screengrabs of the band in previous concerts haunt me driving home. Is the nomadic Vertigo node acquiring a memory of sorts? With the right technology, wouldn't it be possible to build a set that would not only enable but record each performance? Will there one day be a set in some quiet corner of a theme-parked future Dublin, that effortlessly summons up the spectacle of any given evening of a tour? These things have a way of getting smarter, and cheaper.

And if anyone ever does that, I think, it's likely to be U2.